A Dead General, A Bombed Technocrat, and 6-0 Against Peru: The 1978 World Cup and the Argentine Elite

Peru's brief passage through the 2018 World Cup reminded me of the one fútbol anecdote I know about in detail: the Peruvian team's loss to its Argentine hosts in the 1978 World Cup forty years ago today, a match widely considered to have been fixed by a military regime desperate for the reflected glory it would gain by Argentina winning the tournament. A writer for Vice UK wrote a good piece earlier this month that will give you all the facts, including an alleged half-time locker room visit to the Peruvian team by Henry Kissinger, who attended the game as a guest of the Junta. But the background of the story, where fractal internal struggles within the repressive apparatus were linked to the death of the retired Army General originally in charge of the World Cup and the attempted killing of the deputy Economy Minister by a bomb set to blow up at the same minute we scored our fourth goal against Peru, can serve as a snapshot into what made the Proceso such an enduringly pedagogical moment for our upper and upper-middle classes.

One of the most difficult thing to explain about the Proceso is how in some respects it was not a dictatorship at all. Dictators, if we follow the original Roman model, are granted supreme individual authority to secure for the State unity of decision and speed of execution in its policies. Yet after the overthrow of Isabel Peron in 1976, supreme power in Argentina was not decisively wielded by a single executive, but was split rather into three equal parts among the three heads of each of the Armed Forces, as was the formal machinery of state and even the public sphere (different services might assume control of different newspapers, or even create their own). Nor did power flow uninterrupted from the pinnacle of the Junta down to the smallest torture chamber, but was rather parceled out into an archipelago of repressive zones and sub-zones allocated to different commanders responding each to parallel chains of command joined together only tenuously at the top. The "Why" of this mechanism--what were the problems that the Junta was trying to solve by adopting such an almost pre-modern State structure-- would take a separate post to explain, but our famous victory against Peru in the World Cup can give a usefully quick glimpse into the "How."

Argentina had been selected to host the World Cup in 1974. Both the team and the responsibility for organizing the event were one of the many portfolios the military took over after March 24 1976. And, as happened on a larger scale with the direction of economic policy or trade union organization, both became sites for the continuation of inter-service rivalry with the addition of other means. Who would be head coach? Videla, head of the Army and "President" of the Junta, would recall: "We considered [Menotti] a leftist but had basically inherited him. I thought continuity was important in a case like this, so I I didn't want to do what others said and put in someone else, someone more right-wing. Everyone in the Army had their own candidate, and maybe they were good. The Navy was also pushing several names."

But there was a far weightier issue, or at least one that, unlike the choice of head coach, involved a great deal of money. Among the offices awaiting new military overseers on after March 24 1976 was the Autarkic World Entity (Ente Autarquico Mundial, or EAM). This Man-Without-Qualities sounding body had the task of managing all spending related to making Argentina ready to host the World Cup, which, involving as it did construction of new stadiums and improvement of existing transportation infrastructure, would involve expenditure in the millions. Exactly how many of those there would be became a subject of inter-service dispute soon after the coup.

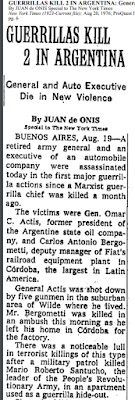

As with all other offices, each of the armed services was guaranteed representation in the EAM. Of its six constituent boards, three were headed by soldiers, one by a sailor, one by an airman and the last one by a civilian. At its head was a retired Army general, Omar Actis, but with a sailor as his deputy, Rear Admiral Carlos Lacoste. The two men quickly came into conflict. Lacoste's spending plans were considered extravagant even by contemporaries, while Actis was in favor of not only a much smaller budget, but also on very tight controls on how it was spent. He would not live to see his version of the Mundial put into effect. On August 19 1976, two days before he was scheduled give a press conference to present his plans, his car was ambushed in a Buenos Aires suburb by a four-man team equipped with automatic weapons and a truck-mounted heavy machine gun. A police station only a few meters away from the attack did not stir. After making sure that Actis was dead, the attackers fled, but not before leaving behind leaflets claiming the action had been carried out by the "Revolutionary Montonero Army," a group nobody had heard of before the attack--nor indeed since. Despite the fact that a high-ranking Army officer had been killed, the news was relegated to the back pages of all newspapers, and the general's funeral was sparsely attended. His deputy Lacoste, who now assumed full control, was not among those present. He presented a much more expansive program only four days later. The 1978 Mundial's cost was eventually put at 517 million dollars. The next one, in Madrid, would come in at 150 million.

As with all other offices, each of the armed services was guaranteed representation in the EAM. Of its six constituent boards, three were headed by soldiers, one by a sailor, one by an airman and the last one by a civilian. At its head was a retired Army general, Omar Actis, but with a sailor as his deputy, Rear Admiral Carlos Lacoste. The two men quickly came into conflict. Lacoste's spending plans were considered extravagant even by contemporaries, while Actis was in favor of not only a much smaller budget, but also on very tight controls on how it was spent. He would not live to see his version of the Mundial put into effect. On August 19 1976, two days before he was scheduled give a press conference to present his plans, his car was ambushed in a Buenos Aires suburb by a four-man team equipped with automatic weapons and a truck-mounted heavy machine gun. A police station only a few meters away from the attack did not stir. After making sure that Actis was dead, the attackers fled, but not before leaving behind leaflets claiming the action had been carried out by the "Revolutionary Montonero Army," a group nobody had heard of before the attack--nor indeed since. Despite the fact that a high-ranking Army officer had been killed, the news was relegated to the back pages of all newspapers, and the general's funeral was sparsely attended. His deputy Lacoste, who now assumed full control, was not among those present. He presented a much more expansive program only four days later. The 1978 Mundial's cost was eventually put at 517 million dollars. The next one, in Madrid, would come in at 150 million.

To question such expenditure would prove to be almost as dangerous as attempting to limit it. Juan Alemann was, as Secretary of Finance, the right-hand man of the civilian Economy Minister, Jose Martínez de Hoz, and embodied like him the elite project of liberalizing the Argentine economy along lines recognizable to any present-day IMF conditionality plan: cut state expenditures, eliminate capital controls, and focus on the export of commodities. For such a figure, what Lacoste had put in motion in 1976 had become intolerable by the time the World Cup came in 1978. In February of that year Alemann gave an interview to a national news magazine denouncing widespread cost overruns, malinvestment, and graft: “The Junta decided to go ahead with the World Cup on the basis of estimates that building and infrastructure works would cost between 70 and 100 million dollars. I doubt that it would have done so had it known that the true cost would be close to 700 million dollars." He went on to complain about stadiums built in isolated locations and of lax accounting practices that had allowed, "waste pure and simple."

To question such expenditure would prove to be almost as dangerous as attempting to limit it. Juan Alemann was, as Secretary of Finance, the right-hand man of the civilian Economy Minister, Jose Martínez de Hoz, and embodied like him the elite project of liberalizing the Argentine economy along lines recognizable to any present-day IMF conditionality plan: cut state expenditures, eliminate capital controls, and focus on the export of commodities. For such a figure, what Lacoste had put in motion in 1976 had become intolerable by the time the World Cup came in 1978. In February of that year Alemann gave an interview to a national news magazine denouncing widespread cost overruns, malinvestment, and graft: “The Junta decided to go ahead with the World Cup on the basis of estimates that building and infrastructure works would cost between 70 and 100 million dollars. I doubt that it would have done so had it known that the true cost would be close to 700 million dollars." He went on to complain about stadiums built in isolated locations and of lax accounting practices that had allowed, "waste pure and simple."

And so on to our storied match against Peru on June 21. In order to qualify for the finals, our team needed not only to win this match, but to do so by a margin of four goals. Two were scored in the first quarter. After a half-time that was the focus on much later conspiratorial theorizing (see the Vice article above), the next two goals came very soon. Three minutes in, Argentina scored its third goal; five minutes, its fourth. And a few seconds after the latter guaranteed that our team would qualify for the finals, a bomb exploded outside Alemann's house: he was fortuitously absent, but his wife suffered minor injuries. To the end of his life he believed that this bomb was retaliation from the Navy for his opposition to the World Cup's cost.

Whodunnit? In a country where even basic numbers about the repression remain a matter of irreconcilable debate, the death of a retired general and a bombing attack against a civilian functionary are unlikely ever to be definitively known. It is more useful to take a step back and consider the kind of regime where even very high-ranking insiders had good cause to fear that internal disagreements might be resolved by means of doorstop bombs or heavy machine guns. For the case of the Mundial was far from unique. To stay with Juan Alemann and the Economics Ministry, early after the coup of 1976 he was the object of repeated menacing visits by generals demanding public money for the provinces or departments they had been newly appointed to, their case strengthened by visibly armed entourages. These visits only stopped only after the Economy Minister made an alliance with General Albano Harguinguy, the Junta's appointment to the the Minister of the Interior (in Argentina as in other Latin countries, a minister of police rather than an auctioneer of public lands). Or take Actis, an Army general (albeit a retired one) killed in a repression zone commanded by the Army. Could internal rivalries be such that soldiers would tolerate a Navy paramilitary commando murdering one of their own? Well, the area was under the jurisdiction of I Corps, a notoriously hardline command that was allied with Massera's Navy in opposition both to the Economy Minister and to Army leadership's project for gradually opening the government to participation by civilian political parties. Their opposition was such that it was only the chance visit to their command post by a high-ranking officer in 1977 that stopped a plot to murder a key aide of Videla, the Secretary of the Presidency Rogelio Villareal, a serving General officer. This was only a few days after the Junta-appointed ambassador to Venezuela, Héctor Hidalgo Solá, a civilian from the conservative wing of the Radical Party, had been disappeared by a Navy commando operating with the collusion of the I Corps leadership.

And here we come to why the Argentine dictatorship may never be the object of the kind of nostalgia with which significant segments of the elite and upper middle-classes in, say, Chile or Brazil appear to view its peers in the 1970s. It is not a difference in the "What?" of mass murder of a limited number of armed insurgents and far larger hosts of labor organizers and leftist activists, nor even the "How?" of torture and disappearances, but rather the "How of the How." Plausible deniability was secured by devolving such murderous autonomy down the chain of command that, once the killing started, the secrecy and compartmentalization of the repressive apparatus allowed individuals within it to turn the methods of State terrorism against members of the elite to resolve disputes over political strategy or even personal enrichment. As Americans can attest after a War on Terror that will soon be measured in decades, civilian establishments are often quite happy to relinquish control over the repressive- and even the war-making apparatus of the State as long as this does not affect their persons, their children, or their wealth. But in Argentina the elite discovered that calling in the military can also lead to the dissolution of the State, both in its Weberian sense of claiming a monopoly of the use of legitimate force and in its Marxian one as the executive committee of the bourgeoisie. Thus sordid, lethal intrigues of the kind that surrounded the Peru-Argentina match in 1978 may have been as important as civilian mass-murder and conventional military defeat in shaping what has proven to be a comparatively durable elite consensus against the advocacy or glorification of military interruptions to civilian rule.