Armies, What Are They Good For? Real-Time Assessment of Peacetime Militaries, Part I: Service Length and the Generals' Job Guarantee

Assessing military quality in real time is difficult because variables that appear self-explanatory in history books yield ambiguous or even misleading results when we try to use them in the present. Will the conscript army you read about in the newspapers flounder like Galtieri's freezing colimbas in the Falklands, or storm all before them like Guderian's panzertruppe at the Meuse crossings? Will a politicized military with parallel chains of command and internal surveillance of officers flounder like the Red Army in Finland in 1940, or advance irresistibly like revolutionary French Army in Belgium in 1795 or the SovietArmy in Germany in 1945? More topically, will 21st century Russian forces perform like those of Debaltseve 2015 or of Kiev 2022?

As this last example shows, maddening variability can bedevil analysis even over quite short periods of time. Conventional opinion about the Turkish Army, "the second largest in NATO", was quite favorable and therefore its initial invasion of Northern Aleppo Province in 2016 seemed so impressive as to be irresistible. However, high tank losses and a stalled advance forced a drastic reconsideration: now, everyone agreed, the force was a shadow of its former self, its upper ranks left bereft of talent by one of the largest peacetime purges ever recorded, remaining generals afraid to tell Erdogan the truth, conscripts either demoralized or so fervently political as to be uncontrollable. Yet what was essentially the same force surprised opinion once more when, two years later, a slow but relentless advance, against highly motivated forces that had fortified themselves for years in mountainous terrain, culminated in complete victory and the destruction of Kurdish Afrin.

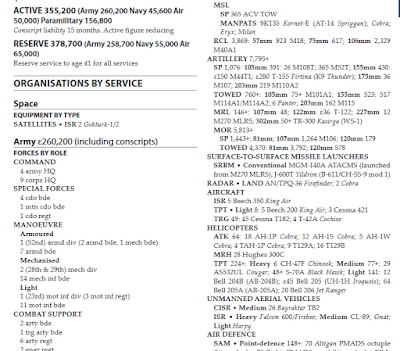

I have thought about this question for more than two decades now across very different contexts: as a precocious journalist working in the shaky Argentine democracy of the 90s through to a superannuated graduate student working on a political science PhD just as counterinsurgency ("COIN") theory reached its apogee in American policy discourse. And I have found that there are some specific, mostly dull factors that can inform what conclusions to draw from those mute totals of soldiers and equipment (such as those in the illustration) through which armies appear to us in the standard reference sources. I will begin this series with what I believe is the most consequential of these factors: the term of service.

The Short-Timers

One of the simplest, most easily-obtainable indicators for military readiness is one that sometimes oddly under-emphasized even in the specialized literature. This is the modal term of service, which is to say how long most of the soldiers will actually serve in the ranks. While this is not the key to all military mythologies, it is a useful solvent for the otherwise ambiguous state of research on what effect an army being professional or conscript has on quality. Effective conscript armies will tend to have a term of service of two years or above, whereas disappointing "volunteer professional" forces will turn out to have contracts of one year or even six months (Colombia in the late 90s and post-Soviet Russia are two examples). This last case (professionals on short contracts) is relatively rare, appearing usually when an otherwise conscript army decides to create an elite "rapid reaction" or deployable sub-component within its order of battle. Because of this, the discussion below will focus on the problems of using short-term conscripts

The first way in which a short term of service adversely impacts military effectiveness is straightforwardly individual. Training will consume so much of a soldier's service that whatever unit he or she belongs to will only be "deployable" during limited stretches of the year. In countries where schooling include paramilitary instruction, such as in Nazi Germany or Soviet Russia, basic training can be shortened to about six weeks, but the approximately 10 weeks used by the modern United States Army should be seen as the more usual standard. Once one includes more advanced training for specialized roles (e.g. heavy weapons, radio, etc.) and to practice tactics at the platoon- and company level, the overall length of time it takes to prepare a soldier can move closer to six months. This means that, for a good portion of any year, impressive-sounding units like a "17th Mechanized Brigade" will be little more than a collection of exhausted conscripts rooming in barracks next to some equipment warehouses.

One useful "Open Source Intelligence" consequence of these short terms of service is that paying careful attention to induction dates can be used to deduce when the army in question will be capable of doing anything more substantial than PT. In her book about the Argentine Army in the Falklands War, Nora Kinzer Stewart described how the strength of the Army varied substantially due to the interaction of a one-year service obligation, the vagaries of the conscript training cycle, and the various furloughs awarded at any given time:

The fluctuating numbers for the Army depend on the number of conscripts inducted each year and on what date in any one of the three training cycles one measures the Army’s size. Conscripts are inducted in March; the training cycle closes in October; a portion of the class is released in November, others in December and January, and the final group after the induction of the new class in March. Therefore, some conscripts serve as few as eight months and others their full twelve-month commitment. Thus the lowest number of men in the Army is between January and March (summer).

Sub-yearly inductions (bi-yearly, quarterly) can be used to make sure that every unit will have a fraction of reasonably-trained conscripts, but this comes at the price of increasing the personnel turbulence associated with recruit contingents coming and going throughout the year. To continue with the Argentine Army on the eve of the Malvinas, some units had begun experimenting with a system of tri-yearly intakes, but even then their "deployable" time-windows continued to be quite narrow. Brigadier Omar Parada had this to say to the postwar Rattenbach Commission about the state of training of his command:

"One third [of the 20-year old] Class of '62 was furloughed, and a third of the [19-year old] Class of '63 was incorporated. When these soldiers finished basic training, they progressed to advanced infantry training. At this stage another third of the Class of '62 was furloughed and a third of the class of '63 incorporated to start basic training. This meant that [by April, when the deployment order to the Falklands was given] the unit was not capable of taking part in any serious conflict. The last group of trained soldiers from '62 were set to leave in July, they were almost all outside the unit, which now consisted almost entirely of the Class of '63, one third of which had only just joined

Short terms of service can have a knock-on effect on officer quality as well. The problem is that a great deal of an officer's year will be spent not in command of actual combat units, but rather as a kind of uniformed school principal, superintending the repetitive transformation of a new gaggle of civilians into a soldiery minimally able to stand on parade and handle their weapons without injury. An article about Russian military reform efforts in the 2000s noted that:

Preserving the draft also distorts the meaning of officers' service, if [the intention of reforms] is to establish the principle of continuous education. After all, officers will be condemned to repeat the basics of combat training with the new recruits each year (if not every six months). For the younger officers, it will be neither possible nor necessary to prove their professional worth [and] it is unlikely that a troop commander will be motivated to improve if he is condemned to cycle through the most basic elements of combat training.

An Argentine officer wrote in a 1988 book about Army reform that "after spending four to six months in the intensive work of training conscripts, officers and NCOs should have available the rest of the year to perfect their own skills and to care for military equipment, duties that can be easily neglected due to the constant demands of recruit training." The time taken up by individual training also means that field maneuvers are often simplified so as not to exceed the capabilities of newly trained soldiers on whatever service time they have left. A field-grade Argentine officer complained to the Rattenbach Commission that his unit had only been able to perform one field exercise involving a straightforward mechanized offensive operation on level terrain, which of course was very different from what it would be asked to do in the Falklands.

More subtly, overseeing a constantly changing mass of people does little to foster cohesion between the officer cadre and the enlisted ranks. This in turn may make it easier for hazing abuses to become so rampant that any "toughening" value is outweighed by morale so low that self-wounding and even suicide become attractive options for the lower enlisted ranks. That is, when abuse is not so harsh as to be outright lethal: in 1993 an incident of this kind solved the problem Lieutenant-Colonel Cruces discussed above by precipitating the outright abolition of conscription in Argentina.

At this point some readers may be wondering why armies retain short conscription terms at all. However sketchily they may be trained, large numbers of soldiers are still quite expensive to house, feed and equip. Would not these resources be better employed to recruit a smaller professional force and outfit it with more modern and plentiful equipment? There two main reasons why this is not done, one respectable and the other less so. The respectable reason is that producing this kind of high-readiness unit, fully staffed and ready to fight at short notice with sophisticated equipment, is, perhaps surprisingly, not what most armies are configured to do.

The Two-Armies Problem or, Ready for What?

Two armies dwell, ach, within most major militaries. One is the barracked, uniformed force available at short notice to occupy a disputed territory or intervene in internal politics. While this has the most salience in people's imaginations, it will often be fundamentally incidental to the second one, the prospective nation-in-arms the country plans to mobilize in case of a major war.

It is in a sense to miss the point of conscript armies when we criticize their peacetime forces as ineffective for short-notice deployments in limited wars. These units are useful not so much in themselves but for the mobilization system they sustain. They are less a force than a framework for force generation. If a major war becomes a possibility, there will be an infrastructure of barracks, warehouses, and instructor cadres to create new units, as well as a pool of trained reservists to ensure that each one will have some soldiers who are not entirely new to military life. The benefit is not merely a faster and larger-sized mobilization, but resilience in the event of ill-fortune on the battlefield. After most of the French Army of 1870, renowned as a force of long-service conscript regulars, became trapped in Metz and Sedan, the new republican government faced difficulties that it never really solved in raising new units, as a demoralizing snippet from a sympathetic British journalist may illustrate:

The Ministry of War... set up training camps all over the country to which troops from the departments were sent before being drafted to the armies in the field. But the camps were hurriedly constructed on ill-chosen sites, were seldom ready in time to house the floods of men sent to them, accommodated them at best in miserable discomfort, and were only able, for lack of instructors, arms and equipment, to provide the barest vestiges of training when they were able to provide any at all. An English journalist visited one training area at Boulogne and reported: "The scene was simply ludicrous. The officers, with one or two exceptions, kept aloof, talking with their friends. . . . Many of the men were engaged in position drill. Then they formed in battalion, and performed sundry evolutions in so clumsy a manner that the officers gave it up in despair, split the battalion into squads of six and ten men, and ordered skirmishing again. . . . 'It is difficult to teach what one is ignorant of oneself,' remarked one officer to another'."

When the army is small as well as long-service and professional, this kind of difficulty will appear even sooner. In 1914, Great Britain used up most of its regular army and reserves to send a five-division expeditionary force to the continent, so that, as Kitchener's call for volunteers brought in hundreds of thousands of new men:

"Regimental depots for clothing, equipping and initial training... were soon overwhelmed.. By clearing married quarters barrack accommodation could be found for 262,00 men. For the rest buildings had to be hired and as many as 800,000 were billeted before permanent camps and hutments could be provided. Similar difficulties were met in clothing. The output from cloth and clothing manufacturers was limited and as an interim measure half a million blue serge suits were made up from Post Office stocks of material. A similar number of civilian overcoats was purchased and issued and recruits with serviceable clothing of their own were required to continue wearing it until uniform supplies became available.

But a key deficiency was human rather than material:

The regiments also suffered from a lack of officers to train them. The government called up all reserve-list officers and any British Indian Army officer who happened to be on leave in the UK during the period. Men who had been to a recognized public school and university graduates, many of whom had some prior military training in Officer Training Corps, were often granted direct commissions. Commanding officers were encouraged to promote promising leaders and later in the war it was common for officers ("temporary gentlemen") to have been promoted from the ranks to meet the demand, especially as casualty rates among junior infantry officers were extremely high. Many officers, both regular and temporary, were promoted to ranks and responsibilities far greater than they had ever realistically expected to hold.

The United States, another proud possessor of a small long-service professional army ("eighteenth in the world after Portugal") would face even greater problems when required to expand into a wartime army numbering in the millions.

Building an army takes more than just opening recruiting stations. Soldiers needed barracks, training areas, uniforms and equipment as well as a steady supply of recruits. The camps needed roads, railroad spurs, sewage, barracks, mess halls, headquarters buildings, hospitals -- all the things that a post needs to function -- and they needed to build them all at once... Equipment was another bottleneck. The first troops showed up and trained with wooden rifles. There were delays in getting uniforms and boots. Heavy equipment or weapons? Nope. Machine guns or artillery? Not really. British and French personnel came to the United States to help train the doughboys, but it was mostly marching, target practice and small unit movement.

But while junior officers and barracks can be improvised, senior officers present a different problem. The regular officer cadre will of course experience accelerated promotion--the 1915 West Point cohort was known as "The Class the Stars Fell On" because so many of its members were in the right place to be promoted to flag-rank during the WW2 expansion--, but will there be enough of them? Furthermore, how would a peacetime experience commanding companies and battalions of hard-bitten regulars translate into commanding and motivating divisions, corps, and field armies made up conscripted citizen soldiers? The solution many militaries adopted after the world wars was to maintain officer corps that were oversize, at the middle and upper ranks, relative to peacetime needs, with its members subject to frequent rotation across units and function. Don Vandergriff has described how this system was formalized in the United States:

In the aftermath of World War II, as Congress began dismantling the greatest force the world had ever seen, Marshall and other senior officers set their sights on demolishing the constabulary method of making war... What they wanted was an excess of officers in the middle grades and senior levels. This cadre officer corps would be composed of "generalists" experienced in a wide variety of command and staff positions. Personnel policies required to create such a cadre involved frequent moves, as many as seventeen in a twenty-year career. This gave officers experience in numerous different duty positions. The rationale was that in time of mobilization, these generalists would be prepared to lead millions of soldiers in new, larger formations because of their wealth of experience. ... The 1947 OPA ensured the army would maintain a larger than necessary officer corps for mobilization purposes—"a cadre army prepared to lead new formations in the emergency of war."

Thus, another function of the skeletal formations we have discussed--"brigades" or "divisions" that are in practice little more a collection of barracks and warehouses--is to familiarize mid- to senior officers with the routines and practice of command. These formations may not be ready for any immediate deployment--after mobilization was declared there would be a great deal of reorganization as reservists are called back to the ranks and trained conscripts split off as cadres for new units--, but they create command- and staff billets where officers can gain invaluable experience in the many roles they may be called upon to fill in case of general war.

Such, in any case, is the theory. But the cynical reader may begin to guess the perverse incentives such a system can create when policymakers are making decisions about the optimal size of an army in a post-Cold War context. Here we arrive at the peculiar political-economic equilibrium many modern armies find themselves in, where short terms of service are maintained in spite of their negative effects on combat effectiveness and with no real prospect of mass mobilization.

A Generals' Job Guarantee

The empirical regularity by which armies are becoming increasingly top-heavy-- with greater numbers of senior officers relative to the total number of troops-- is a subject deserving of its own post. For now let us focus on how this trend can be linked with the existence of low-readiness formations of dubious wartime utility.

The end of the Cold War confronted many armed forces with an HR problem. Reducing the number of major military formations (be they divisions, major naval combatants, or air force wings) demands finding something to do with newly redundant general-rank officers (and the field-grade officers on their staff), as well meritorious up-and-coming subordinates now deprived, by sheer budgetary bad luck, of what should have been well-deserved command billets.

However, in the military as in business and academia, it can be difficult for the subset of employees making decisions about downsizing to downsize themselves. One way or another, a way will usually be found either to shield decision-makers' posts from cuts, or to create suitable alternatives. In Western militaries, headquarters positions--whether "Joint", international, or simply at different technical directorates--have become useful for parking officers the organization does not want to lose to retirement, whether voluntary or mandated by "up or out" promotion systems. These jobs are neither good nor bad in themselves --indeed, we will see in a moment that "field commands" can be as hollow as any of the office assignments known within the Royal Navy as "Flag Officer Parking Lots"--, but their existence has allowed the number of senior-officer jobs to remain relatively stable even in the most ferociously-downsizing armed forces in the West, leading in many cases to historically unprecedented levels of senior officers relative to army size.

But it is much more common for the number of senior posts to be intimately tied to the number of command positions and, therefore, to the size of the order of battle. Our "17th Mechanized Brigade" may indeed consist of barely-trained conscripts living next to an army warehouse, but it nonetheless provides gainful employment for a brigadier-general in command and attendant colonels and lieutenant colonels on his or her staff, while a "III Corps" or "2nd Army" made up of such units would demand at least a Major-General at its head. We have seen in the previous section that it can be useful for senior officers to have this kind of administrative experience, but the persistence of such barely-functional units in a geopolitical context favoring high-readiness professional forces suggests irresistibly that corporate self-interest among officer corps must play a role.

Even before the recent war in Ukraine, the Russian Federation afforded the most consistently fascinating spectacle of this tension. Let us be topical and conclude this article with an examination of how even the most autocratic Russian heads of state have had to struggle against an officer corps for whom a high-readiness, intervention-capable army represents, oddly enough, a professional threat.

To Every Colonel According to his Needs: The Professional Politics of Military Modernization in Russia

The Russian experience of the Second World War seemed to confirm the wisdom of a military system where successive classes of conscripts serving a substantial but still relatively short term of service would produce, over time, truly vast reserves of trained manpower. But, essential for wars of national survival, this system encountered all kinds of difficulties when called upon to generate forces for anything more limited or unexpected. Even in the late Cold War period, a high proportion of the millions of men that appeared so terrifying from west of the Oder-Neisse were extremely difficult to employ,

In the later Soviet period, [their] 203 divisions were never all fully manned. Only 50 Category A divisions were described as being at “permanent readiness.” The rest, the B, C, and D category formations, were cadre units; understrength and waiting to be filled out only on mobilization. The division’s category depended on its manning strength and equipment schedules. A Category C division would, for instance, have a personnel strength of approximately 1,000—mainly officers and warrant officers.11 In the post-Cold War era, the situation in terms of these divisions’ manning levels became considerably “worse.” Only some 13 percent of the ground forces’ overall assets were now deemed ready to take part in immediate operations (i.e., without mobilization).

It should be added that those "permanent readiness" divisions were not equivalent to such specialized rapid-reaction forces as the US 82nd Airborne or the British Commando brigades, specifically configured for short-notice "out of area" expeditionary deployments far from their peacetime garrison areas. If Moscow ever faced a military emergency that was not a major ground war against NATO along the Iron Curtain, those "Category A" units were not actually "ready" to be sent to a distant, unexpected theater of war. If they had been, they would be leaving a gaping hole in the Red Army's order of battle in case a conventional ground war did break out against NATO (or China). Instead, the Russian military would choose both in 1979 and later to implement a kind of draft-within-the-army, combing existing units for combat-ready soldiers that would then be sent to the actual theater of war, there to be cobbled together into composite Afghanistan- or Chechnya-only formations.

[D]uring the Soviet engagement in Afghanistan in the 1980s the battalions sent there (infantry, airborne, artillery, etc.) were all composite in nature: that is, they were not distinct units but had rather been brought together in ersatz fashion from the personnel of the three undermanned battalions that made up any standing Soviet regiment. So one Soviet regiment (without mobilization) was only ever actually able, it seemed, to muster just one battalion... The problem carried on into the new Russian era. . . . The battalions, for instance, being sent to Chechnya in the 1990s were also composite in nature. Operational efficiency naturally suffered.

Russian leaders had then some cause for impatience even before the fall of the Berlin Wall and later the financial upheavals of the 1990s created irresistible pressures to downsize the armed forces. Would it not be possible both to increase military capability and win popular support by replacing conscription--with its seemingly ineradicable and often lethal dedovschina hazing of draftees -- with a volunteer professional system in the manner of most Western armies? Proposals to that effect were not just made but formally adopted under Yeltsin in 1992-93 and 1997, and under the new Putin regime in 2001 and 2003. In a retrospective study of an even later reform initiative, Charles Bartles observed "Russian military reform has followed a fairly predictable pattern since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Russia's civilian leadership's mantra of military reform is modernize, downsize, end conscription, and increase servicemen salaries."

That what was essentially the same reform effort had to be re-introduced so many times is testament to the deep resistance it encountered among the senior military leadership. Although the ostensible objections went from conscription's nominal role in the patriotic education of Russian citizens to the needs of a war against NATO, analysts over the years have concluded that a concern with professional self-preservation played a significant role.

It [may not be] obvious why Russia's military commanders would want to undermine efforts to introduce even a small number of volunteer units into the military force structure. After all, militaries containing both professional and conscript personnel are common in Europe. Several countries with "mixed" systems-for example, Hungary, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland- also maintain sizable reserves....[S]hort-term universal conscription ... lends itself to a top-heavy officer corps--Russia's military ranks currently have more colonels than lieutenants.... A transition toward a professional military would necessitate a wave of forced retirements at the highest levels... In most cases, officers who achieve the rank of general have endured 30 years of political scrutiny and institutional indignities to receive their stars. The prospect of being stripped of this status prematurely cannot be welcome to those in question.

Even under the supposedly autocratic Putin government, the military was able to delay if not altogether stall the transition to a "contract" volunteer force. In a speech in 2006, celebrating what he clearly believed was a successful reform effort, Putin recalled how at the start of the Second Chechen War :

In order to effectively respond to the terrorists, we needed to assemble a force of at least 65,000 men. And in the whole army, in the combat-ready subunits, there were 55,000, and those were scattered across the country. The army had 1.4 million people, and no one to fight. And here they sent unseasoned boys out under fire.

However, the unexpected outbreak of war with in Georgia in 2008 revealed that the armed forces were not in a much better state, with one officer recalling how

"We had to search one person at a time for lieutenant-colonels, colonels or generals throughout the armed forces to participate in the combat operations in Georgia, because the table of organization commanders (paper divisions and regiments) was simply not in a state to solve combat issues."

Ultimate victory in that war had been, for insiders, too much of a near-run thing. The Defense Minister at the time was Anatoly Serdyukov, whose appointment in 2007 had been hailed as "the first true civilian Defense Minister, as he had no ties to the Armed Forces or Security Services", but his "first year had been fairly lackluster, and it appeared that his tenure would be much the same as his predecessor[s]--lots of talk, but few results."

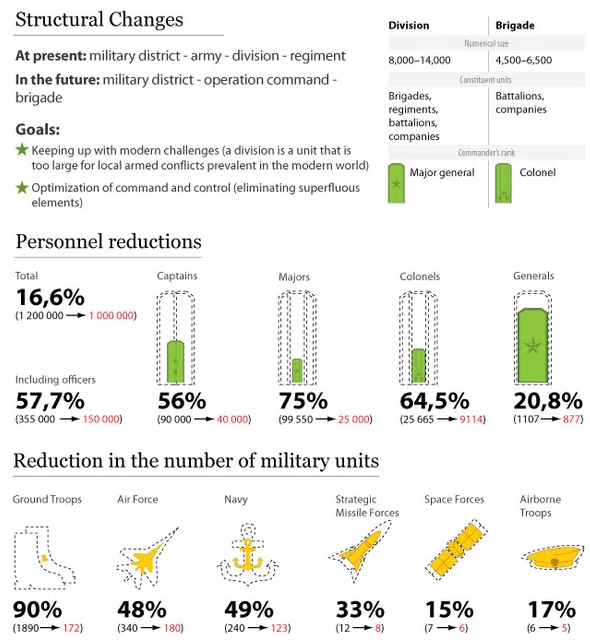

Serdyukov put pressure on the Ground Forces in particular. His questions were the same as those in the Yeltsin era. Why did it still have its 203 divisions when by now the overall size of the military had come down to approximately 1.2 million? and how could these 203 divisions produce, it appeared, only 90,000 combat-effective troops when technically they should be capable of putting 1 million men into the field. The answer was still the same and it was still simple: if there were 203 divisions then they would still be needing 203-divisions' worth of generals to command them. Serdyukov could find all the corruption he liked, but he could still not shift the structure of the 203 divisions.

This time, however, the alarming military unreadiness exposed by the Georgian emergency tipped the scales, and Serdyukov was able to accomplish possibly the most consequential reform effort since the fall of the Soviet Union. Interested readers are encouraged to read Charles Bartles 2011 paper on the subject, but for our purposes it is enough to note that (a) it required a great deal of re-shuffling or forced retirement of senior officers, as well as the importation of civilian officials from Serdyukov's previous appointment in the federal tax authority, and (b) this time reform did indeed make a significant inroads in the size of of the Russian officer corps.

The key was that reduction in the number of ground forces units (visible in the lower-left corner in the image) was critical. Many of these "cadre" units were in effect a kind of job guarantee for literally tens of thousands of middle-upper ranking officers, as Rod Thornton has explained:

[W]hile all these divisions were lacking in conscripts, what they did not lack was officers. These were still there acting in their role as the divisions’ cadre strength. Thus there were divisions with only 1,000 or so personnel; half of whom would be officers or warrant officers. This was the obvious result of putting the fox in charge of the chicken coop. For here was a ruse by the military hierarchy to preserve officer posts: units needed officers—including generals—and so the units were kept.

... While the officers in such cadres had very little to do for the most part, the system they were part of did provide employment for tens of thousands of them--including many generals. Any move towards a smaller, professional military would, naturally enough, create far fewer reservists--both because there would be fewer professionals serving and because they would be serving for longer. The patent result would be that a good proportion of the mass mobilization structure would have to be cut, along with the jobs of those officers who were part of it.

It would take us too far afield to discuss the further consequences of the Serdyukov reforms and the state of the Russian military prior to its invasion of Ukraine in 2022 (a 2014 article by Roger McDermott identifies some continued weaknesses that still detectable today). But I hope it is now clearer why the short-term of service, however many and varied its problems in terms of military effectiveness, remains so stubbornly persistent in modern armies.