Notes on Real-Time War-Watching

I need first to apologize to my subscribers for the delay in publishing. I was one of the many people caught by surprise by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and this quite upended my plan to open the newsletter with an in-depth post about the importance of terms of service to military effectiveness. However, while that specific post will have to wait for another week, a more immediately useful one can be written on the same theme of how to gauge, in real-time, military variables that appear as obvious and self-explanatory in history books. I will therefore detail below some observations I have made over the decades--first as a journalist reliant on wire reports about Kosovo or Iraq and then as an online watcher of conflicts from Syria to Nagorno-Karabakh-- about how to back out substantive information out of such chaotic palimpsests of information as confront us today about the war in Ukraine.

"Is this a little or a lot?": Casualties

Reliable casualty figures at this stage of the war are essentially a contradiction in terms. Let me start with the few cases when something can be deduced out of such numbers as are published, before detailing the dangers of reading too much into even the most reliable of them.

Official announcements are useful in that each side will usually minimize their own losses, so any figure admitted in official communiques can usually be counted on as a floor or baseline for whatever the actual number may turn out to be. Thus, when I read a report from the Russian Ministry of Defense announcing that Russian forces have suffered 498 killed and 1597 wounded, I am reasonably confident in using that number as a minimum for Russian casualties. (Note, however, that there is a contrary incentive regarding civilian casualties: the more one's own side civilians have been killed, the greater a propaganda case that can be made about the brutality of the other side, so the tendency in official announcements is often inflationary rather than deflationary.)

It is useful too to pay attention to credible details regarding the losses that a specific unit may have suffered. Numbers will still have huge error bars around them, but one may be able to deduce something substantive out of them. For example, if there are reliable figures that a certain battalion tactical group suffered 73 soldiers killed, then one can use a (very) conservative estimator for the number of wounded (x2), and arrive at a probable total figure of 219 losses, and then compare this figure against the nominal strength of such a unit (600-800) and conclude that this unit may have suffered something close to 50 percent casualties and is likely either combat ineffective or close to being so.

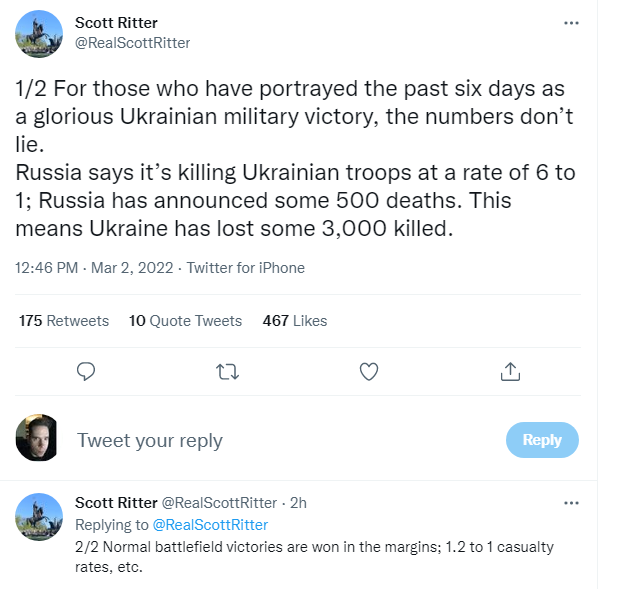

But there are hard limits to how much one can deduce, from such partial or official totals, about the course of the war. As it happens, while writing this post I came across an example of how even intelligent analysts can go wrong in this regard.

Alert readers will instantly jump on the phrase "Russia says it's killing Ukrainian troops at a rate of 6 to 1" and they would be quite right. With the best will in the world and no intent to deceive, military units invariably overestimate both their opponents and the losses they inflict on them. Even if I were the Russian command I would not necessarily trust the estimates my units are sending up the chain regarding Ukrainian numbers or losses. However, Ritter's conclusion would be questionable even if it had been based on some magically declassified archival sources from both the Russian and Ukrainian sides.

First, casualty "exchange ratios" (so many of side X killed or wounded for so many of side Y) are generally to be used with extreme caution, if not considered entirely useless without abundant evidence in their support. First, there's a STAT 100 problem of aggregation: does that that 6:1 ratio apply equally to a Donets/Lukhansk separatist force holding out in entrenched positions as to a mechanized BTG blundering towards Kiev? To take two famous incidents of the Normandy campaign, I see from Wikipedia that the exchange ratios for the battles of Omaha Beach and Cherbourg were, in terms of Allied casualties per one German casualty, 4.1 (5,000:1,200) and 0.59 (22,000:37,000). Do I pick one or the other as more "typical"? Or do I aggregate all totals (27,000 total Allied casualties against 38,000 German) to arrive at an entirely synthetic figure of 0.71? If I have the option (and both analysts and journalists on deadline might not), I would do neither.

Even more risky is to generalize "at this rate" into conclusions about total casualties. I would be extremely careful of using estimates such such as Russian or Ukrainian forces "have suffered X,000 KIA", whether estimated or aggregated from individual news reports. There seems always to be a great demand for total casualty figures that I find rather mysterious. We usually do not know what the denominator of total combat troops is, so it is hard to determine, to use a favorite question Terry Moe liked to ask at Q&As, "is this is a little or a lot?". As time goes on and the number and sources for casualty information increase, the significance of total estimates become even more nebulous. If the force in question continues to fight, does it matter if someone deduces their casualties to date have been X,000, X0,000 or even X00,000?

One rationale is to develop what Vietnam-era American Generals termed the crossover point, or the point at which the enemy begins to suffer more casualties than they can replace. That this measure had high salience during the Vietnam War (as well as within Douglas Haig's intelligence staff during World War 1) may be warning enough in itself. In general, armies can stay fighting longer than total-casualty analysts can retain their credibility, and high losses may themselves lead to policy changes negating earlier estimates of available manpower.

Over the course of the Syrian civil war there was a great deal of faintly ghoulish interest in whether the losses of the Syrian Arab Army were such that, cumulatively, they exceeded the number of Alawites and amenable Sunni Muslims available to replace them. And analysts duly found signs that such a point had been reached in 2013 . . . and in 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018 as well. In themselves these reports are no more laughable than warnings from heterodox economists about the American real estate market that appeared before the actual crash in 2008. Both detected a real empirical phenomenon, and in a sense it is our own responsibility as readers not to read such reports as making definite predictions about whether a given "unsustainable" situation (whether mortgage-based securities' valuations or Syrian Arab Army's force generation) will actually cease to sustain itself in the near future. In the case of the SAA, the numerical weaknesses detected as early as 2013 were quite real, but the consequence was not eventual collapse as units dwindled in size enough for them to be defeated, but rather a change in strategy focusing consolidation of loyal areas rather than offensives to retake rebel-held ones, and an increase in the use of foreign fighters, from the excellent Hezbollah expeditionary units to the much more ill-trained (but useful enough for garrison purposes) Shia militias from Iraq and Afghanistan.

But what about the effect of casualties on home front morale? Will high enough losses lead to a loss of support in Russia or Ukraine? My answer will usually be on the side of "no" for two reasons. The first one involves time again: domestic political opposition to long and costly wars in general take much too long to stop the fighting at any given point. But the second is, as Peter Feaver perceived quite correctly before 9/11, that what domestic publics consider "unacceptable" casualties is usually entirely conditional on their impression of how well the war in question seems to be going. In an American context, an additional one thousand dead in Iraq and Afghanistan can be entirely tolerable in 2004 but a sign of unacceptably costly stagnation in 2015.

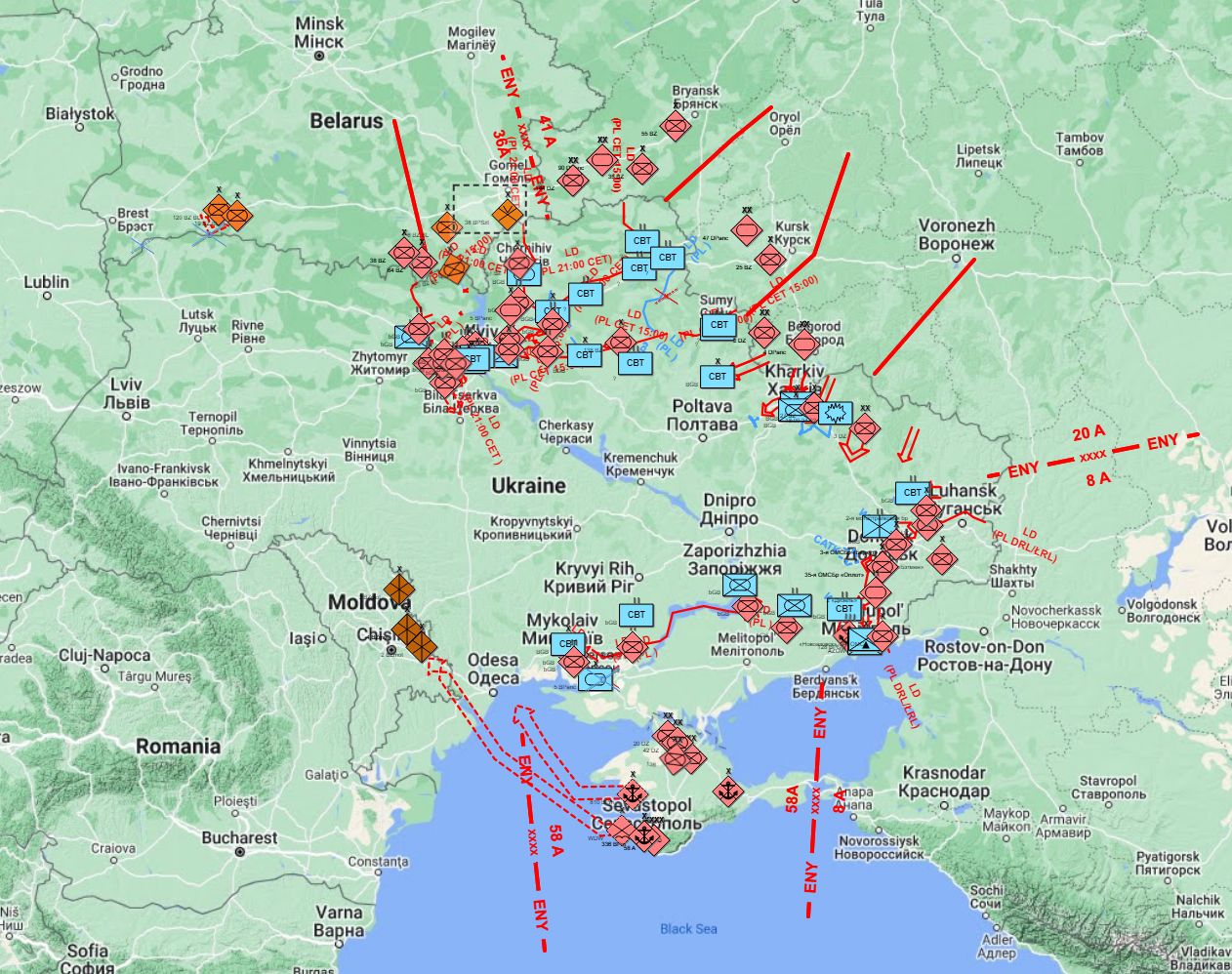

"All Attempts to Capture 'B' Have Been Bloodily Repulsed": Following the Map

A way to break out of the futile spiral of casualty estimates is to look at the map and remember that conducting an offensive in modern warfare will usually be a very costly proposition even if you're successful. It is entirely ordinary for individual front-line units to suffer (in the abstract) crippling casualties, but for the offensive as a whole to continue because there are more combat units to put in as reinforcements. The advancing units might be suffering "heavy losses", but if the names of the villages being fought over keep changing, then clearly these casualties have not stopped their army as a whole. (BORGES: "In wartime 'Desperate enemy attempts to capture B have been bloodily repulsed' is how you admit that A has fallen.") The above-mentioned assault on Omaha Beach was ultimately successful, however high the kill:loss ratio in favor of the German side.

Keeping track of control changes on the map is also a good way of saving oneself from reading too much into abundant video clips or reports of successful ambushes, destroyed APCs and dead soldiers lying around them, etc.. These can really be deceptive. I saw during the Nagorno-Karabakh war that many people who wished the Armenians well (perhaps the Armenian command as well) were cheering themselves up with reports, more or less accurate, about Azeri light infantry suffering quite heavy casualties from surprise barrages and ambushes as they advanced through the mountains. This was fine, but, as John Griffiths wisely observed regarding light tanks designed to fight delaying actions, a side that is conducting a lot of ambushes is a side that is probably retreating a lot, and in most theaters of war there are key strategic points or lines of supply that will eventually become compromised. In Nagorno-Karabakh, the Azeris had indeed enough force behind their push in the southern sector that they were eventually able to cut off the main pro-Armenian forces from Armenia proper, and win the war.

In his invaluable Strategy: The Logic of War and Peace, Edward Luttwak, using the hypothetical case of deploying cheap missile-armed infantrymen against a Soviet armored assault against NATO, described very vividly the logic by which a sequence of seemingly bloody or "pyrrhic" encounters can, with no contradiction or paradox, amount to what is operationally an overwhelmingly successful offensive.

As we seek to estimate the effect of antitank missile infantry among the many-sided interactions of the operational level, we now recognize that the fight between the armor unit and the missile unit that we watched at the tactical level is quite inconclusive by itself... For as we widen our view, we see that behind the first unit of Soviet tanks and mechanized infantry there are many more, forming a deep column waiting to fight their way through the front. What we learned at the tactical level continues to be true, but the meaning of this truth is transformed: the Soviet armor that the missiles are destroying is there, in a sense, precisely to be destroyed, as it destroys launcher teams in turn and exhausts their stock of missiles. The tanks and combat carriers are not merely firing ammunition, they themselves are ammunition, which the penetration column is expending to clear the way for its own advance. Of course the Soviet army would rather lose less than more in breaking through the line, but so long as the passage through the front is achieved, the tactical result, that "exchange rate," is unimportant at the operational level--if is indeed only one defensive line. The success or failure of the ensuing deep-penetration offensive will not depend on whether the advancing forces as a whole have lost 5 or 10 percent of their numbers as the price of entry into the vulnerable rear areas.

Recall, finally, that it is a perfectly ordinary military activity to launch attacks not to break through but rather to hold enemy forces in place and ideally draw in additional reserves. The significance of these attacks is to be measured not in the loss ratio between the opposing forces, but rather what decisions elsewhere in the theater of war are made possible by the absence of soldiers who are fighting in what, it will eventually transpire, was a secondary front. (Indeed, it was German practice in both World Wars not to inform subordinate commanders about whether their attacks were meant as holding operations: it was thought that the latter would be all the more convincing a distraction if carried out by commanders who believed they were part of the main effort.) To bring up the example of Nagorno-Karabakh once more, some of the encouraging combat footage and reports of successful defense came from the northern and central sectors of the front: these were entirely correct, but they were entirely consonant also with the main Azeri thrust taking place in the south with the objective of cutting off the enclave from Armenia proper. To extrapolate the course of the war from the fighting in the center and north would have been as misleading as noting that most of the actual attacks on the Maginot Line in 1940 were repulsed.

I have tried to keep away in this post from judgements about the specific course of events in Ukraine, but the case of the fighting by pro-Russian separatist forces in the Donbass area is simply too useful an example to let pass. Exactly what is happening on this front is obscure, but one can still conclude that anything the pro-Russian side does, hopeless attacks repulsed with ten times as many casualties as the enemy suffered, will be justified if it keeps mobile units of the Ukrainian army fixed in that area and unable to respond to breakthroughs and threatened encirclements elsewhere. It is another reason to keep a map handy whenever one reads about individual engagements.

Readers interested in exploring how severe and embarrassing tactical defeats can occur in the midst of total victory are encouraged to read Ernest May's Strange Victory about the fall of France 1940. From the opening of the campaign in the Low Countries to the closing stages of "Plan Red" against French resistance south of the Loire, there were many instances not merely of tactical defeat but of hastily-trained reservists recalled to Wehrmacht infantry units proving to be quite as shaky as their equivalents in infamous "Series B" French reserve infantry units.

Bergson at War: Time, Duration, and Stalemates

Readers of Proust may be familiar with the Bergsonian distinction between time and duration, between a quantified sense of how long something lasts and the qualitative experience of actually living it. Such reveries are actually extremely useful to keep in mind when coming to conclusions about the course of any war one is following in real-time. What in a history book will feel almost instantaneous when described as "the offensive slowed down in X, the enemy resisting stiffly for two days before finally being pushed back to Y" can feel like ages if, as most of us are probably doing, one is constantly refreshing social media and live maps to follow a war hour by hour. This in turn can lead to misleading perceptions that an offensive has "stalled" in a World War One sense, especially when there are a lot of reports floating around about how "the enemy suffered 762 losses today".

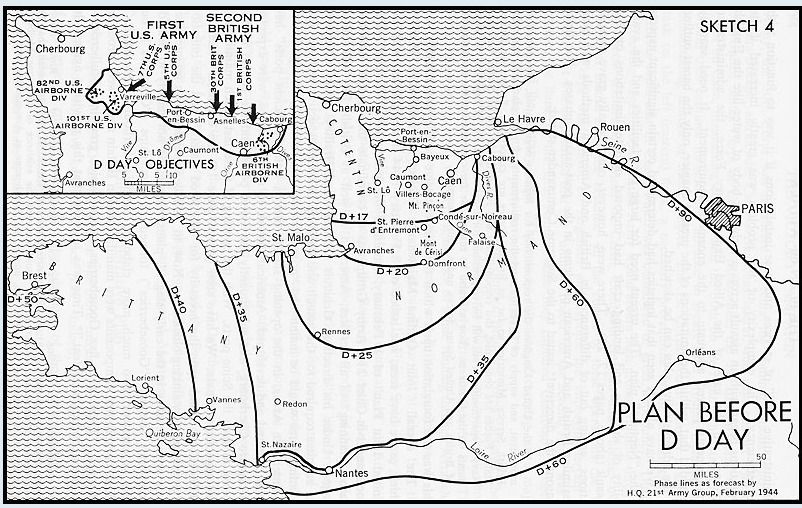

But remember that offensives do not proceed linearly over time, an advance of X miles in Y days will not necessarily occur in neat increments of X/Y miles per day. A famous example was the Normandy Campaign controversy between SHAEF headquarters and Montgomery (in his capacity as ground forces commander) about the pace of the advance after the D-Day landings. Looking at the phase lines established during the planning process, Eisenhower's staff became increasingly agitated about how, looking at the front-line, the offensive seemed to be badly behind schedule on D+10 or D+20. However, after the German Army broke in the Falaise Pocket, the Allied armies eventually advanced far ahead of where these phase lines suggested they would be on D+90 (Seine already crossed, British approaching Belgium, etc.). People who followed the 2003 invasion of Iraq may remember there was some anxiety, even predictions of defeat, when the American offensive slowed down near Nasiriyah and some other crossings of the Euphrates.

I warn about all this not because I have any definite opinion about what is happening right now in Ukraine, but because I have seen in a number of conflicts now, from Syria to Nagorno-Karabakh, that people can develop false hopes from the frontlines not moving much over a set period of days. This lack of movement may reflect a genuine defeat of an enemy offensive, but it could also be an attritional phase of unpredictable length that can occur in any close-fought battle. Unfortunately it is usually only possible to distinguish these things in retrospect, the only operational advice I can give is to retain a Popperian agnosticism about any impressions you may derive from observing the progress of the conflict from a distance.

Logistics and Morale

One final note concerns impressions of the effectiveness and morale of the adversaries in war. At a time when the outcome of the war is in doubt, when there is not much movement on the map, casualty numbers are one thing for the anxious mind to focus on, but another are reports about traffic jams, desertions, incompetence, and other factoids that become enticing as potential keys to an underlying reality that may decide the conflict. This post is becoming quite long, so I will confine myself to two points.

The first is that there is a great deal of "friction" in war, even the most successful campaigns will have many cases of what an uncharitable eye could construe as hopeless disorganization, traffic jams for example having accompanied even the most successful campaigns in history.

Friction is the only conception which, in a general way, corresponds to that which distinguishes real war from war on paper. The military machine, the army and all belonging to it, is in fact simple; and appears, on this account, easy to manage. But let us reflect that no part of it is in one piece, that it is composed entirely of individuals, each of which keeps up its own friction in all directions. Theoretically all sounds very well; the commander of a battalion is responsible for the execution of the order given; and as the battalion by its discipline is glued together into one piece, and the chief must be a man of acknowledged zeal, the beam turns on an iron pin with little friction. But it is not so in reality, and all that is exaggerated and false in such a conception manifests itself at once in war. The battalion always remains composed of a number of men, of whom, if chance so wills, the most insignificant is able to occasion delay, and even irregularity. The danger which war brings with it, the bodily exertions which it requires, augment this evil so much, that they may be regarded as the greatest causes of it.

So far so very platitudinous, but one should keep in mind also that most modern peacetime armies are simply not habituated and sometimes not even prepared to advance far beyond their own borders. There are two general causes. One is that in peacetime armies dispose of an enormous amount of "slack" in the form of civilian infrastructure and specialist personnel that, at a pinch, can be used to coordinate and complete movements and ensure the flow of supplies. This in turn can encourage militaries to focus excessively on "teeth" (combat) as opposed to "tail" (logistics) units, not least because no politician or nationalist citizen becomes terribly excited by adding more motor pool battalions to the order of battle. It also makes mixing and matching units into "task organized" commands seem considerably easier to do than it would be in enemy territory. In combination, all this means that there can be quite surprising logistical breakdowns whenever a force is ordered to move into enemy territory. Future posts will be relying possibly to excess on the example of the Argentina in the Falklands War, so here I will merely note that both the Israelis in 2006 and the Turks in 2016, neither especially feckless militaries, suffered severe logistical breakdowns less than 50 miles from their own borders.

The second point is that "morale" is a highly situational variable. An excellent unit in a hopeless position may surrender because its destruction by artillery fire would not accomplish anything, while a poor defending unit may fight to the death because it fears the other side is not taking prisoners. To make general judgements about the "fighting spirit" of an entire army or even nation from local decisions to fight or surrender is an extremely uncertain enterprise.

Actual defection in combat is a tricky thing to pull off under most circumstances absent active collaboration from the command cadre. Allied operations analysis people estimated, after studying the performance of those static "German" units in Normandy that were composed mostly of former Soviet POWs or "Volksdeutsche" who could barely speak the language, that a battalion-sized unit could be effective in defensive operations even when only 20 percent of its troops were actively loyal. If one thinks through the mechanics of what a combat unit, one can begin to see why.

In quiet times, to supply a force is necessarily to control and surveil the force as well; without a lot of unscheduled movement, it is easy to determine if a soldier wandering around the rear area is not where he is supposed to be. Modern engagement ranges are pretty high, so making your way to the enemy's frontline will take a bit of doing, and a deserter crawling to avoid being shot by his own side may look, to a nervous sentry, like a dangerous infiltration patrol that should be destroyed. In action, engagement ranges are also a problem: if you're a machine-gunner who doesn't open fire when told so then you'll be shot. Once you start shooting, however, as far as the enemy's concerned you may as well be some fanatic determined on a last stand, and in all wars people who try to surrender only when the enemy gets close do not usually enjoy high survival rates.

Finally, Collective Action Problems Rule All Around Me. For subordinates to coordinate common action in defiance of their formal superiors is difficult whether you're talking about infantry companies or Starbucks coffee shops. The more efforts subordinates make to organize themselves, the more likely this is to be noticed by management, and the greater the risk that any one worker or soldier may find it advantageous to "defect" from common purpose in exchange for lavish individual reward. This means that a great deal of discontent and even active disloyalty can be masked under the guise of apparently "stable" units.

I will close with another quotation from Luttwak, from his lesser-known 1985 The Pentagon and the Art of War. The first impulse will be to extend his warning to people underestimating the Soviet Army's modern successors, but the exact same points could be made about for their opponents on the Ukrainian side (pro-Russian online sources are as enthusiastic as everyone else to detect low morale and incompetence in their enemies):

Entire books have appeared which argue that the Soviet Armed forces are much weaker than they seem. Citing refugee accounts or personal experience, they depict the pervasive technical incompetence, drunkenness, corruption, and bleak apathy of officers and men. Drunken officers and faked inspections, Turkic conscripts who cannot understand orders in Russia, drownings in botched river-crossing tests, the harsh lives of ill-fed, ill-housed and virtually unpaid Soviet conscripts, and a pervasive lack of adequate training fill these accounts.... But there is much less in these accounts than meets the eye.

Very similar stories of gross incompetence can be heard from anyone who has ever served in the armed forces of any country, even the most accomplished. When one assesses the actual record of war, not from official accounts but rather from those who were there, it becomes quite clear that battles are won not by perfection but rather by the supremacy of forces that are 5 percent effective over forces that are 2 percent effective. In peacetime, when all the frictions of war are absent, when there is no enemy ready to thwart every enterprise, effectiveness may reach the dizzy height of 50 percent--which means, of course, that filling in the wrong form, postings to the wrong place, supplying the wrong replacement parts, assigning the wrong training times, selecting the wrong officers, and other kinds of errors are merely normal. Matters cannot be otherwise, because military organizations are much larger than the manageable groupings of civilian life that set our standards of competence; and because their many intricate tasks must be performed not by the life-career specialists who run factories, hospitals, symphony orchestras, and even government offices, but by transients who are briefly trained--short-service conscripts in the case of the Soviet armed forces.

[D]runkenness is no doubt pervasive in the Soviet armed forces. But Russians have always been great drinkers. Drunk they defeated Napoleon, and drunk again they defeated Hitler's armies and advanced all the way to Berlin. ... On the question of loyalty even less need be said. Should the Soviet Union start a war, only to experience a series of swift defeats, it is perfectly possible that mutinies would follow against the Kremlin's oppressive and most unjust rule. But if the initial war operations were successful, it would be foolish to expect that private disloyalty would emerge to undo victory and disintegrate the armed forces. There will always be a small minority of lonely heroes with the inner resources to act.. [but] the rest of us weaker souls stay in the safety of the crowd--and the crowd will not rebel against a uniquely pervasive police system at the very time when successful war is adding to its prestige, and the laws of war are making its sanctions more terrible.

Thank you for reading, and I hope to establish a more regular scheduling of posts in the coming weeks.